Ash Testing

In 2016, over the course of several months, I built two studios in our back garden. My own ‘micro studio’ and a larger space for my multi-talented wife, also an Artist, who runs Art and Animation workshops for children.

The build journey was pretty epic for someone who had no prior building experience beyond some rudimentary furniture making and the odd bit of stud walling in various Artists’ studios over the years.

You can learn more about the build in this Instagram Story Archive.

For several years after, we have had a metal dustbin/incinerator, almost brim full with wood ash, sitting in our garden where I had burned up the scraps of construction timber left over from the build.

When I finally stopped to think about it, I realised that this benign bin of ash held a certain sentimental value. - It was a kind of celebratory act, at the end of a long week, to sit with a beer staring into the flames of these scrap fires, contemplating the progress, or lack of, and dreaming about the final fit-out. In some ways, the ash marks the achievement of the studio builds as much as their presence, or the output or enjoyment they now give us.

And so I decided to make use of even this sentimental byproduct, by developing a series of ceramic Ash Glazes.

It is a remarkable idea that something so seemingly final as ash, can itself be transformed by heat, and made to melt, but that is the promise of a Wood Ash Glaze, and the goal I would pursue.

Having read around the debate, I decided not to ‘wash’ my ash. - I took the stance that I wanted to keep as much of the natural character of the Ash as possible, and if that meant mixing only small batches of dry ingredients up as and when they are needed, then that was fine. (Unwashed ash still contains many soluble materials and when stored, wet, in a glaze bucket for months, these materials leach out and can therefore change the firing characteristics of the glaze. - It is also quite caustic.)

In keeping with this approach, I selected pure kaolin and silica for the other two ingredients of my first triaxial test. Normally one might select a clay with a bit more ‘personality’ but, again, the ash is the star here.

Ash glazes have been a staple of ceramics, both high-end studio ceramics, and humble utility pottery for centuries. Plant ash is cheap and happens to include many of the chemical/mineral elements and compounds needed to make a glaze. Unfortunately there is a particular stereotype which associates ash glazes with that oh so “brown” pottery made by slightly gruff bearded men wearing itchy sweaters in idyllic English country village potteries.

Some of the romance of that stereotype does form part of my fascination with Ceramics and its History. But ash glazes are also alluring for their simplicity (they often only need one other ingredient to form a glaze), and their variability.

Each plant yields ash which varies considerably, not just from, say, oak to beech ash, but ash from one oak tree to another, so this means every batch of glaze is unique. This unique character means that extensive testing is required, and also brings a sense of mystery reminiscent of oenology and viniculture. What might my unassuming bin of grey muck produce?

A triaxial test involves testing every possible combination of three main ingredients in set increments. Here I am making a 66 point test meaning that each ingredient is combined in 10% increments. This involves weighing out 165 individual ‘doses’ using a gram scale. I tried to be as accurate as possible, and gave myself a tolerance of plus or minus 0.03g with this batch.

With considerable time and effort already invested I packed the kiln and set them off to 1280°C. Each 100g sample had a dash of Sodium Dispex to deflocculate the mix and allow fluidity at a lower water content. And each test tile has a thinner layer painted on the left side and more to the right.

Five strong candidates for further testing

The results were more than I could have hoped for, and immediately that I brought them out of the kiln room, into the light, I could see that there were several promising candidates for future development. From granular granite greys, to a soft velvety green-grey with blooms of orange crystals, right through to fluid glassy green-browns. Indeed the 100% ash sample was surprisingly complete as a glaze.

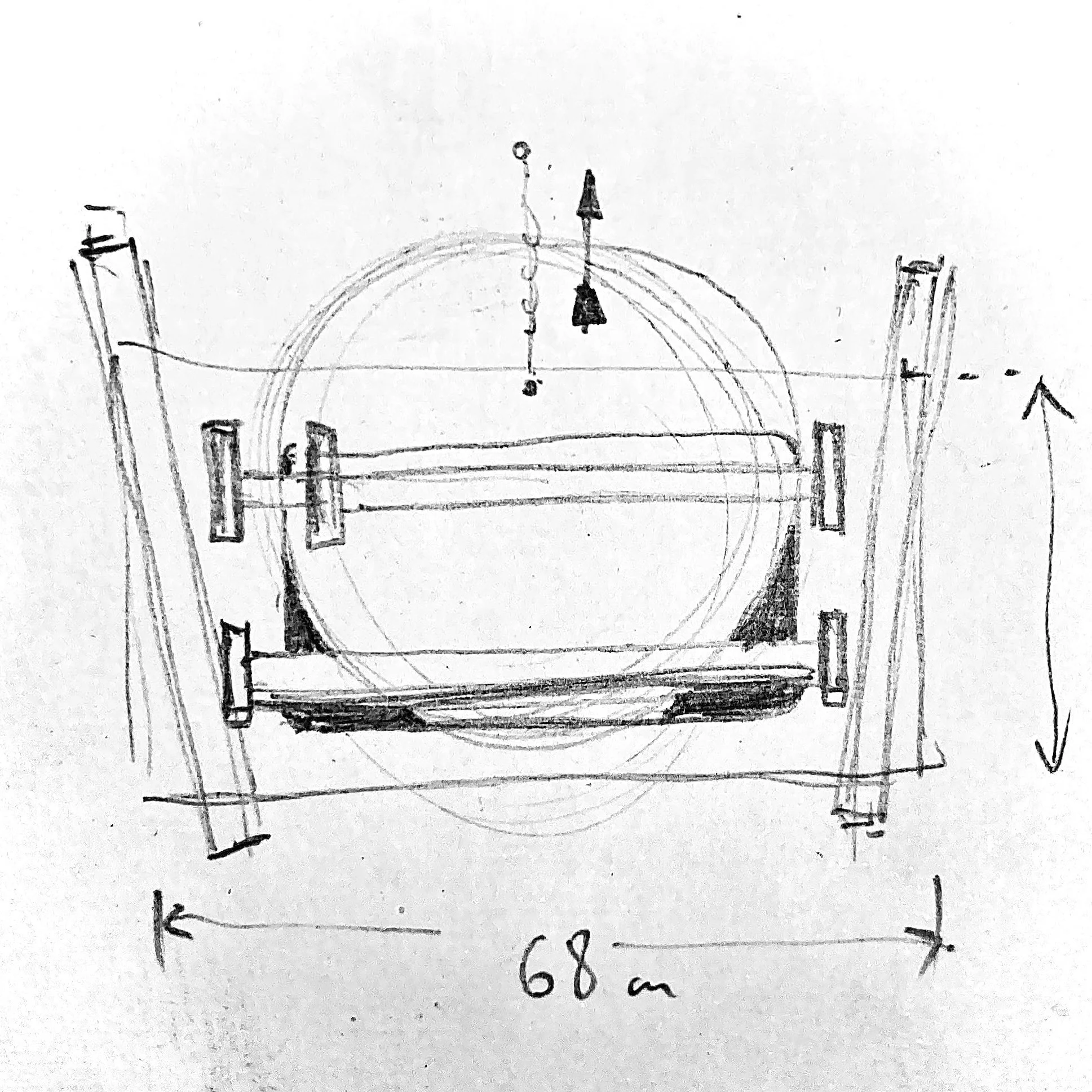

Owning to how richly varied and mottled these glazes are, I began to think (for the first time!) that I might glaze some work entirely using just one glaze. - This open mouthed moonjar, from the Orbit series has the dryer, granite-like glaze on the outside, and the slightly more fluid version which promotes the orange (rutile?) crystal growth, on the inside: